How was the Lambeth Conference? is the question which will be asked of everyone who was there in the coming days and weeks.

It was wonderful! I met the Church in many places and contexts, through the extraordinary gift of gathering and deep conversation with sister and brother bishops from all over the world, as we told our stories and listened to the stories of others living in incredibly different situations and cultures.

I heard again the big story of how Christ is encultured in every nation; how the Gospel translates into the intensely patriarchal cultures of Australian Aboriginal nations, living with the grind of poverty and endemic racism; into the remote villages of the Amazon where land rights are regularly ignored and abused; and into the lives of the indigenous people of Alaska, where the caribou have been displaced from the coastal plains where they calve and where the salmon are no longer able to swim upstream on the Yukon river to spawn. It was an amazing experience to meet the bishops who minister in these places and among these people – each one a loved child of God – and who preach hope and work for justice and reconciliation. My dozens of encounters with other bishops and their spouses were both broad and deep, and I was deeply moved and inspired by what the Anglican Church is facing and is doing across God’s world.

We heard again the good news that we are one in Christ; that we are enough and that we have enough. We talked about the dangers the world faces, and encouraged each other in our role as shepherds, each doing our best to tend Christ’s precious flock with humility and courage.

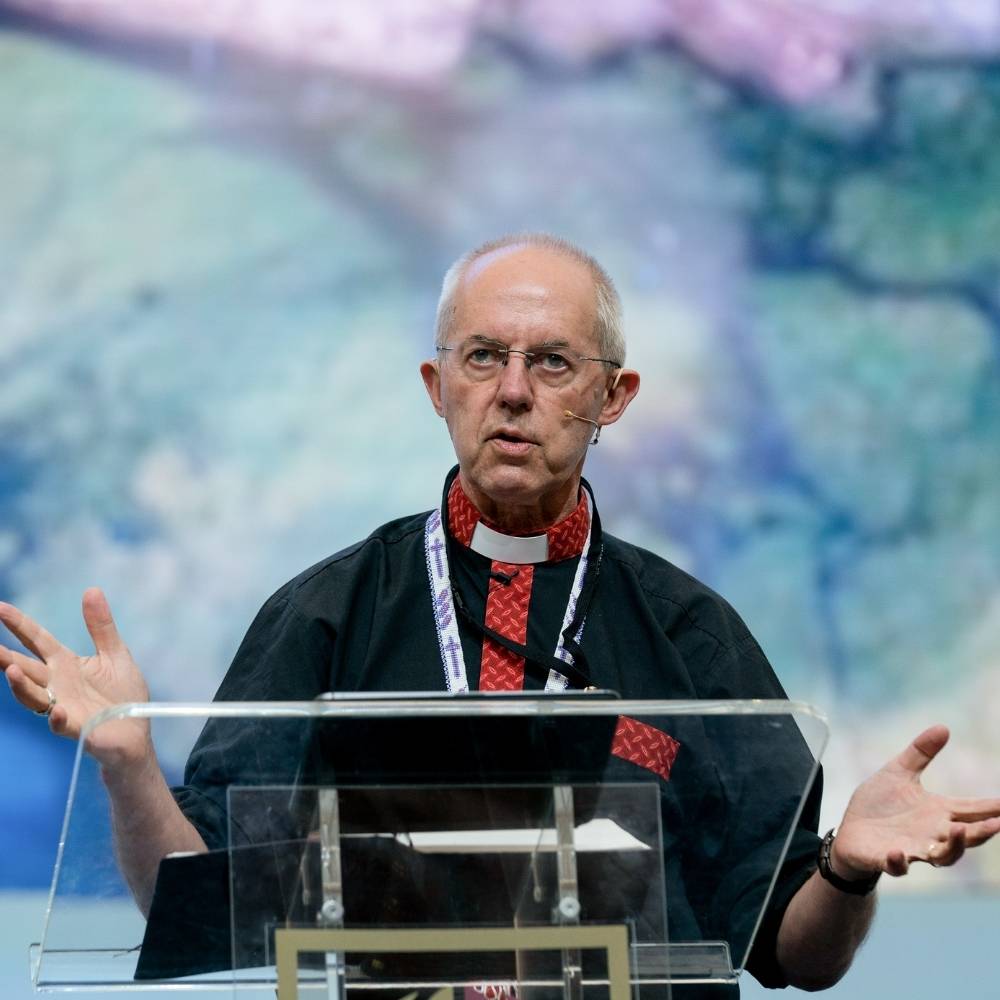

You will not be surprised that I was particularly focussed on the environmental strand of the Conference. Archbishop Justin reminded us of the seriousness of this as he repeated the prediction of the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) that by 2050 there could well be between 800m and 1.2bn climate refugees – those who have been forced to leave their homelands because climate change has made it impossible to stay. And that if we reach the levels of warming which are predicted on our current trajectory - 2.5-3.2 degrees – it will take human beings well past what is survivable in many parts of the world. Every fraction of a degree counts. The Church – and that means each one of us - is a major player in avoiding the worst scenarios. And we are already acting across the globe.

The Conference saw the inauguration of the Communion Forest, with a symbolic tree planted at Lambeth Palace. The Forest is a call to the Anglican Church in every part of the world to take part in tree growing; forest protection, and ecosystem restoration. These are practical and spiritual acts, because to plant is to hope; to protect is to love, and to restore is to heal. We need to think about how we respond locally to this call.

The Conference saw the inauguration of the Communion Forest, with a symbolic tree planted at Lambeth Palace. The Forest is a call to the Anglican Church in every part of the world to take part in tree growing; forest protection, and ecosystem restoration. These are practical and spiritual acts, because to plant is to hope; to protect is to love, and to restore is to heal. We need to think about how we respond locally to this call.

Elizabeth Wathuthi – a young climate activist from Kenya – told us the story of the hummingbird who tries to put out the forest fire by carrying a drop of water in her beak, over and over again, watched with derision by the elephants who tell her that the task is impossible. But they are won over by her determination, and join the struggle, filling their huge trunks with water. The task is not hopeless. Everywhere the Church is speaking out, acting, and helping people to survive and adapt.

I heard of the Church’s prophetic challenge to the people of Kansas where the prairie grasslands are being degraded or monocropped, and where huge commercial and political forces give out a constant message about the primacy of power and profit. The large land holdings of the Church are being repurposed into community spaces as the Church speaks out against the sin of biodiversity massacre and finds ways to live differently.

Over dinner, I talked with a bishop from Madagascar and his wife. They told us of the terrible drought in their diocese and how people are desperately hungry. The church is acting as a conduit for food aid but the provision is patchy. They are concerned that people will become permanently dependent on outside assistance. But the Church is working with people to help them to develop resilience to the changing conditions, and it is starting to make a difference.

The Bishop of Amazonia, whose diocese contains the ‘lungs of the planet’, spoke of the terrible effects of the environmental crisis on her indigenous congregations – the furthest of which is 30 hours travel by boat, where the dangers come not only from below the surface of the water but also from pirates which operate on the river. She works closely with the Catholic church to fight for land rights alongside indigenous people, whose forest is being cleared and cultivated by powerful outside actors, and who are being killed when they voice opposition. It takes huge courage and faith to speak out against these forces of exploitation and environmental destruction.

In Kenya, as in Sudan and other parts of Africa, the seasons have changed and the weather is no longer predictable. People do not know when to plant their crops Rains are delayed, not by a few days, but sometimes by a few months, and recently they have failed entirely. People are hungry, and the church is responding - Those who have more give to those who have less. It all feels much like Paul’s collections of money in Antioch and other places for the relief of suffering in Jerusalem.

I could go on. There were many other stories, striking in the way that God’s people are finding hope, courage, and even joy in the most difficult of circumstances.

Less than a year ago, the newest Province (the 42nd) in the Anglican Communion was formed – the Province of Mozambique and Angola. There are 5 new missionary dioceses in Mozambique, and I met the bishop of the Zambezia diocese. He shared some of the issues which they are facing. Transport is a huge challenge for clergy in his diocese, where the roads are poor and seasonal and there is little public transport. Stipends are very low and although there are only 11 parishes so far, each has dozens of outstations, some of them very distant. The outlying congregations are run by lay people and they can only have the Eucharist, or baptisms when the priest visits. The priests are under pressure to take out loans to buy a motorbike, but the repayments dig deep into a stipend which has to support his wife and children. But the bishop has asked each congregation to collect a little money each year to enable the diocese to buy one motorbike a year to help avoid the priests taking on this debt. They have just bought the first one and are on the way to the second. The church is growing fast.

I wept with my brothers and sisters from South Sudan – where the gospel is being shared against a backdrop of poverty, violence and insecurity; where people live in daily, and nightly fear, and rape and death are facts of everyday life. The Bishop of Rejaf, the rural area surrounding Juba town, has a wife and 5 children. But there is no education for them in his diocese, so two are in Egypt and his wife and 3 younger ones are in Kampala. He is alone in a very challenging ministry. The Bishop of Liwolo continues to lead his people even though most of them are now living in a refugee camp in northern Uganda. But Christ is present, and people are turning to him daily in numbers. There is joy as well as suffering.

The Indigenous church in Canada is very fragile and has been beset with many problems, but Archbishop Linda Nicholls is determined that they will find a way to raise up its leadership and strengthen its structures. The Christian churches in Canada, as in Australia, did terrible wrongs to indigenous people by removing their children to residential schools to eradicate their cultures and languages and teach them ‘Western’ ways. These little ones suffered terrible abuse, many died. And shockingly, no one said ‘this is wrong’. We, in the arrogance of our Western assumptions, inflicted unbelievable suffering, as both the Pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury have publicly acknowledged.

Indigenous voices are crucial for us to hear, not only because they have much to teach us about the Christ who came to save us all, but also because they speak with wisdom and clarity about the stark realities of climate change as it affects the most vulnerable people in the world. If we are to fully understand and tackle the global environmental crisis we must work together.

Indigenous voices are crucial for us to hear, not only because they have much to teach us about the Christ who came to save us all, but also because they speak with wisdom and clarity about the stark realities of climate change as it affects the most vulnerable people in the world. If we are to fully understand and tackle the global environmental crisis we must work together.

The Archbishop of Canterbury’s addresses to us were powerful and clear. He reminded us that we were meeting in a time of world crisis, a time of war, unrest, violence, poverty, and a global environmental emergency and that Christ is calling us to deeper discipleship. If we spend too much time looking inward rather than outward, we will fail in our calling.

Much has been made of the differences which exist within the Communion. But what shone through every encounter I had in Canterbury was the firm reality that far more unites us than divides us. Our time together, in worship, prayer, Bible study, discussion, conversation and sharing meals was a seedbed of empathy and love. How can we not love each other when we have spent time trying on each other’s shoes?

My conclusions? There is much to process, but I have come home all the more convinced that we need each other; that God’s purposes are far greater than my small mind can fathom; that it takes the whole world to know the whole Christ. As Archbishop Justin said, we must stop our civil wars – there are enough wars in the world. We have a common identity which is over everything; we are one in Christ.

My heart has been enlarged; my sense of God has been enlarged; my love for the Earth and all that is in it has been enlarged. And for that, I am profoundly grateful.

+Olivia